14 Jul Cumulonimbus Clouds

Cumulonimbus clouds are considered the absolute kings of the cloud world. Cumulonimbus clouds are commonly known as thunderstorm clouds, and while the bases of these clouds sit between 1,100 and 6,500ft usually.. they are the ONLY cloud in the world that takes up the entirety of the atmosphere. In fact, on rare occasions they can grow high enough to push through the troposphere into the stratosphere – they are the only cloud which has the capabilities to do this. However, they often hit the top of the troposphere and then spread outwards producing a large anvil cloud. They can sometimes also be referred to as thunderclouds, thunderheads of or thunderstorms.

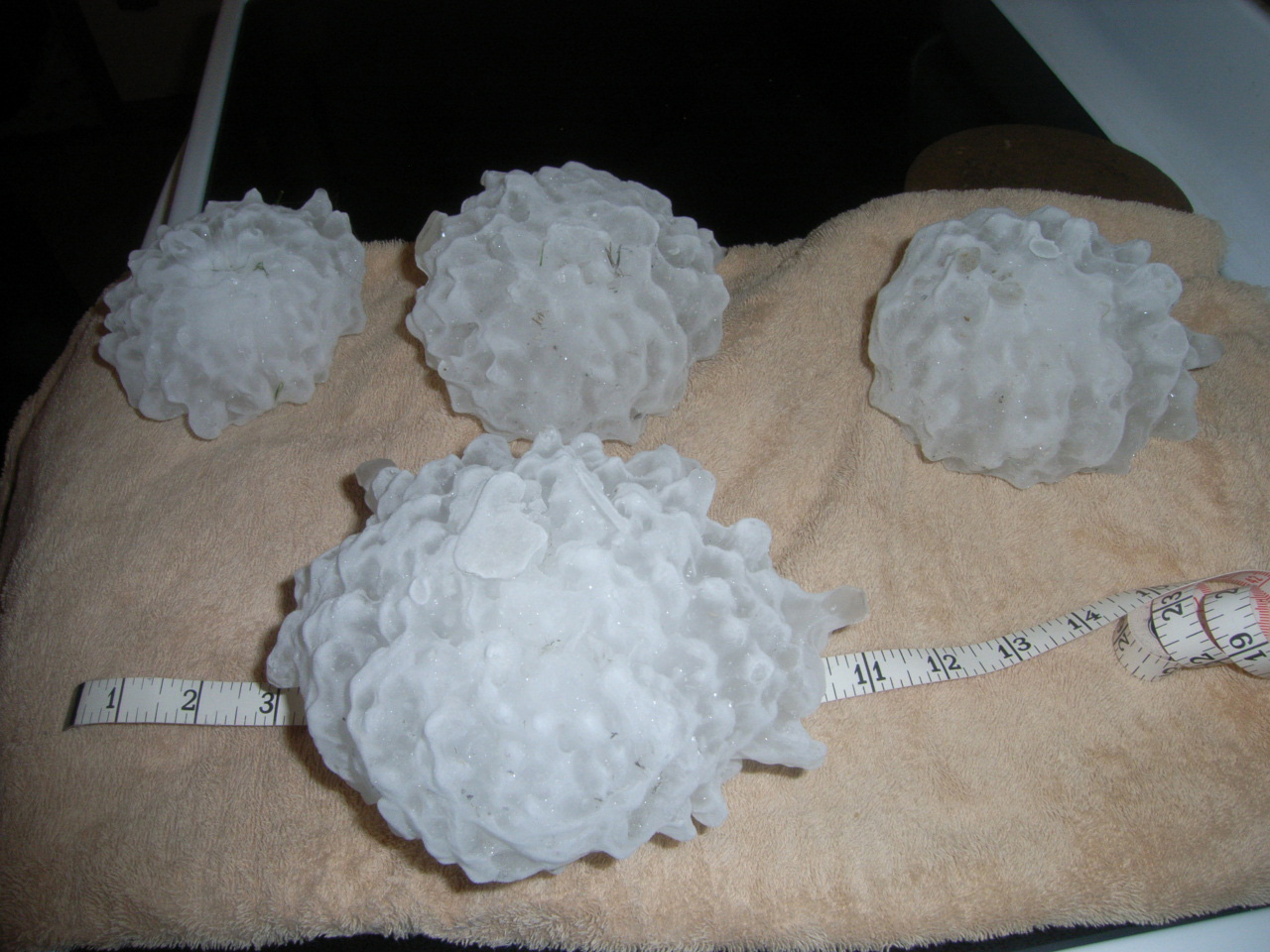

These types of clouds produce the heaviest and fiercest precipitation on planet Earth which can include heavy to even torrential rainfall which may lead to flash flooding or river flooding, hailstones which can become extremely large along with non-precipitation features such as thunder and lightning. The bases of these clouds is usually flat, but can be extremely well defined and may only lie a few hundred feet above the surface in the nastiest of circumstances.

Wall cloud captured by NZP Chasers

Cumulonimbus clouds develop through convection and often begin their life as innocent white fluffy puffs known as cumulus clouds which sit in the low levels of the atmosphere. As the heating of the day progresses and moisture remains or increases with temperature, the capping inversion above the surface of the earth dissipates or breaks, and allows the cumulus clouds to grow into towering cumulonimbus clouds. All the energy and power stored inside them then drives them to potentially last for several hours at a time where they can produce some of the most dangerous weather on Earth.

Cumulus field over the Arizona Mountains via Marc Cooper

As stated above, cumulonimbus clouds can produce heavy to torrential rainfall which may lead to both flash and river flooding. They can also produce hailstones, which can often reach up to the size of baseballs or softballs during the peak of the United States storm season and tennis balls or greater in the Australian storm season. They can also produce dangerous, very frequent lightning, damaging to destructive winds, deafening thunder and in the harshest of circumstances… tornadoes. While most cells less between 30 and 60 minutes, some can last more than 10-12hrs. Regardless of the duration, any cumulonimbus cloud has the potential in the right circumstances to become a danger. Some of these can be single cellular which last for a shorter duration of time, while others can become multicellular which can last for a much longer period of time. The longest form of these is typically a supercell thunderstorm which has the capabilities of producing destructive to very destructive winds, giant to monster size hailstones, torrential rainfall and tornadoes.

Tornado in Eastern Colorado captured by HSC Admin Thomas in June 2015

Cumulonimbus clouds can be categorised into 3 different types of clouds, and while each has its own individual characteristic which separates it from the rest… they all come from the same base mechanics which make them part of the cumulonimbus family. These categories are Calvus, Capillatus and Incus.

-

Cumulonimbus Calvus: The tops of these clouds are quite puffy like cumulus clouds. The water droplets at the top of the cloud however have not become frozen.

-

Cumulonimbus Capillatus: The top of these clouds are typically fibrous, but relatively contained. Water droplets have started to freeze and usually indicate that precipitation has either begun or will begin shortly.

-

Cumulonimbus Incus: The top of the cloud is both fibrous and anvil shaped as the cloud continues to grow it reaches the top of the troposphere and is forced to grow outwards rather than upwards. This creates the anvil-shaped appearance.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.